Every throwing athletes wants to throw hard. But how do you do it? What can athletes do to effectively and safely increase their velocity? Let’s talk through some of the biggest factors that play a role in velocity enhancement and how to leverage those factors to increase the numbers on the radar gun.

As a rehab facility, we have seen many athletes who have experienced catastrophic injuries while attempting to gain velocity with a velocity training program. Unfortunately, many of these programs are built on the idea of solely increasing arm speed and lower body strength, as if those are the only factors that translate to velocity enhancement. Contrarily, there are numerous factors that contribute to increasing velocity and it is of the utmost importance to correctly identify which factors are prohibiting each athlete from seeing the increases in velocity that they should be seeing.

The first, and most vital component of safe velocity is the efficiency of YOUR throwing mechanics. The biomechanics of the throw dictate how well you generate/produce force, how well you transfer energy throughout your kinetic chain, how well you are able to stabilize joints, etc. Understanding how these factors complement one another is the key to unlocking untapped velocity.

As a former collegiate and professional pitcher, I myself have ran through a plethora of different throwing programs to try and increase my velocity. Unfortunately, many of these programs led to arm pain, decreased accuracy, and reliance on “throwing” rather than “pitching.” Sure, you may see initial increases in velocity due to neural adaptations from the training you are doing, but these initial increases in velocity are not sustainable long term.

As I mentioned above, these initial increases are typically due to short-term neural adaptations without tissue or movement pattern adaptations. This is why velocity nowadays is so inconsistent. I see time and time again, athletes who hit a certain number in a facility or showcase, and then in game, they are nowhere close to where they were. Why is that? Because in a closed environment, with no hitters in the box, no competition, it is easy for an athlete to throw with one goal in mind: Throw hard. Whereas in a game situation, there is much more on the table such as various game situations, hitters strength/weaknesses, execution, etc.

As a thrower, improving your kinematic sequence, the positioning of your joints, the ability of your muscles to produce high levels of force, and the timing of when your muscles contraction will not only increase your velocity, but can also decrease the amount of load being applied to the delicate structures of your elbow and shoulder. This allows for sustainable velocity gains with a decreased perceived effort (“free and easy”).

There are certain attractor states (states of stability) that throwers should obtain during the throw such as flexing the elbow inside of 90 degrees during layback, abducting the shoulder between 85 and 100 degrees at foot strike, maintaining -10 to 0 degrees of horizontal abduction at foot strike, and many many more. You will see that most elite level throwers move through these stability parameters during the throw.

In a study from the Journal of Applied Biomechanics, researchers found that three kinematic parameters were significantly related to increased throwing velocity (Stodden, 2005). Those parameters being decreased shoulder horizontal abduction (no arm drag or pushiness) at foot strike, decreased shoulder abduction (elbow height) during acceleration, and increased forward trunk tilt (chest forward) at release. These are all major states of stability (attractor states) that help to make a throwing motion not only more stable but also more efficient and powerful.

Another vital component of increasing velocity in a safe and sustainable fashion is rotator cuff, periscapular, and flexor/pronator strength. As a biomechanics specialist, most athletes I see do not possess adequate strength in these areas to withstand the loads of the throw or maintain stability throughout the duration of the throw.

The role of the rotator cuff is to provide stability within the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint). If there is weakness or malpositioning of the shoulder, these muscles cannot fire to stabilize the glenohumeral joint in the way they are meant to. This can lead to erratic movement inside the joint causing labral pathology, rotator cuff tears, and can transfer higher loads to the medial elbow or other soft tissues.

In another study by the American Journal of Sports Medicine, researchers found that athletes who experienced arm pain presented with lower levels of strength in their dominant arm’s posterior shoulder musculature, ie the rotator cuff, when compared to their non-dominant arm (Trakis, 2008).

Not only does this strength discrepancy increase the likelihood of injury/reinjury, but it also decreases the rate of speed your arm can move at due to a lack of stability that results in energy dissipation.

Athletes often believe they are doing “arm care” when completing low level, generic exercises that are not specific to the loads of throw. We see athletes doing rotator cuff exercises incorrectly all the time which leads to inconsistent results and is one of the reasons why we have spent so much time designing a program to ensure these exercises are done properly. Technique of each exercise is of the utmost importance.

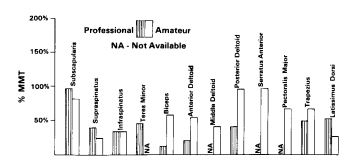

When analyzing muscle activity profiles of elite level throwers compared to amateur throwers, we see large discrepancies which not only aid the elite throwers in throwing harder but also help them prevent injury.

During the deceleration phase of the throw, amateur athletes have increased usage of mover muscles such as posterior and anterior deltoids, pec major, and traps which are contracting to try and stabilize the shoulder because the rotator cuff muscles are too weak to do so. All of those mover muscles are not made to stabilize joints, hence the name, but rather move a lever from one point to another. When you try and make muscles do something that they are not designed to do, that is when tissue degradation and decreased efficiency occur.

A factor that is commonly overlooked in throwing is flexibility/mobility. The first thing to note is that flexibility and mobility are not the same. Mobility, as it is commonly used in the strength and conditioning profession, refers to one’s ability to move through 3-dimensional space (meaning flexibility + motor control + strength). Many have attributed this to moving a joint through its full range of motion with control, stability, and without restrictions. Flexibility, on the other hand, is the range of motion of a joint or joints. It represents the ability to access various ranges of motion actively or passively, statically or dynamically. Understanding that difference is essential when attempting to understand deficits in movement capability and where they originate from.

Decreased range of motion in different joints can cause compensations in mechanics, increased impulse loading on soft tissues and joints, and decreased arm speed all of which increase likelihood of injury while simultaneously decreasing velocity.

For example, lack of shoulder internal rotation range of motion can decrease the rate of acceleration of the arm as it moves from the late cocking phase into the acceleration phase of the throw. Lack of internal rotation can also decrease the deceleration arc of the throw which will increase the impulsive loading of the posterior rotator cuff and periscapular musculature as these structures contract to slow the arm down. The less time tissue has to absorb load, the higher the reactive impulse is that is being applied to those tissues. Think of the way a brake system works on a car, if you have less time to brake, the brakes must work harder to slow the car down in a shortened period of time. The slowing down of the arm works in a similar way, but in this case, the shoulder and muscles attached to the scapula become the brake system… or in this case the break system. Repetitive excessive loading leads to tissue breakdown and eventually injury.

In order to rectify the various deficits of an athlete it is a requirement to implement specific biomechanical retraining techniques. To improve flexibility numerous techniques can be employed such as static passive stretching, dynamic stretching, lengthened partials, and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques. These techniques aim to lengthen muscles and increase the extensibility of soft tissues, promoting a greater range of motion. To optimize mobility during training, it is essential to integrate corrective exercises into your routine that maximize agonist and antagonist strengthening at the limit of range of motion in positions required for throwing. Corrective exercises address muscle imbalances, postural issues, and movement dysfunctions that may hinder mobility. By identifying weak areas and addressing them through targeted exercises, you can improve overall movement quality and maximize mobility.

Ultimately, the factors that play a pivotal role in limiting velocity can be different for one athlete vs another. It is important to identify which factors, specifically, are limiting YOUR velocity recruitment and then target those deficiencies aggressively. This is why it is important to get evaluated by a biomechanics specialist who can help your properly identify these deficits as well as help you structure a training plan to get you where you need to be!

Stodden, D. F., Fleisig, G. S., McLean, S. P., & Andrews, J. R. (2005). Relationship of Biomechanical Factors to Baseball Pitching Velocity: Within Pitcher Variation. Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 21(1), 44-56.

Trakis, J. E., McHugh, M. P., Caracciolo, P. A., Busciacco, L., Mullaney, M., & Nicholas, S. J. (2008). Muscle Strength and Range of Motion in Adolescent Pitchers with Throwing-related Pain: Implications for Injury Prevention. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(11), 2173-2178.

Gowan, I. D., Jobe, F. W., Tibone, J. E., Perry, J., & Moynes, D. R. (1987). A comparative electromyographic analysis of the shoulder during pitching: professional versus amateur pitchers. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 15(6): 586–590. doi:10.1177/036354658701500611